Over 370 participants gathered at CIIS to honor Jung’s 150th birthday in a transformative exploration of psyche, purpose, and collective healing.

Laverne Cox and the Urgent Pedagogy of Survival

The transgender frontier icon spoke at CIIS

We were on our feet long before Laverne Cox walked onto the stage. Karim Baer, Director of Public Programs & Performances, introduced the evening, shouting out the LGBTQI organizations that helped with the event. He told us who was in the theater with us, and who had tried to be in the theater with us: an activist in London who had heard about the event and raised funds to ensure that young trans people who might not otherwise be able to attend, could, and two trans activists from Sudan who couldn’t get visas. “We’ll get them here next time,” Baer promised.

“As a university, one of the things that we want to do is use arts and ideas to promote change,” Baer continued. “We wanted to honor Laverne, and what better way to celebrate Women’s History Month than by hosting Laverne Cox.”

The audience of 1,200 cheered. Then we quieted long enough for him to introduce Theresa Sparks, Executive Director of the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, and the first trans woman named “Woman of the Year” by the California State Assembly.

“We need to change the public’s perception of how they see us and who we are,” said Sparks. “Media is the most powerful way to do this. We need strong voices, and courageous spokespeople—and we need them to be visible. Laverne Cox is one of those individuals emerging as our face, our voice, and our very integrity.”

Cox stepped onto the stage to a standing ovation. As she and Sparks hugged, we stomped and clapped, refusing to sit down. Cox walked toward the edge of the stage and took in our excitement.

“Thank, you. Thank you,” she said, as we finally settled down. Cox looked out into the audience and immediately greeted two heroes in the house: Cecilia Chung, senior Strategist at Transgender Law Center and San Francisco Health Commissioner, who was just named the 2014 “Woman of the Year” by the California Legislature, and Miss Major, a veteran of more than 40 years of community organizing and service, now the Executive Director of the Transgender Gender Variant Intersex Justice Project (TGI Justice).

Miss Major, who is an elder to many community members, took part in the Stonewall Uprising and became politicized while incarcerated in Attica prison. Cox said that without trans women like Miss Major, she would not be standing in front of us. Tears welled in Cox’s eyes and all of ours.

What we hope for is an academia that holds in its heart the belief that a pursuit of a just world is not in conflict with a deep inquiry.”

Intersecting Oppressions

Cox told us her life story: her relationship with her twin brother and their single mother, her experience of intersecting oppressions as African American, working class, and gender non-conforming. She talked about how as a young person she internalized the pervasive transphobia and racism in the culture around her, which led to her despair and suicidality. Fighting to create a life as a writer, actor, and dancer unfolded into an acceptance of herself—and fueled her fierce insistence on survival.

Cries of assent and “Amen, sister!” were shouted so loudly from the balcony that often we couldn’t hear Cox. And maybe that was the point of the night: an African American transgender woman standing onstage at the Nourse Theater talking to a full house, asserting the agency and necessary survival of women, of people of color, of transgender people. Of all of us. Maybe invoking this overwhelming roar to drown out or join her voice was exactly the point.

As Cox preached to the full theater, my queer activist friends and I looked at one another, our eyes wide. This would not be one of the talks we’d heard from Hollywood celebrities about their adopted social justice causes, and it would not be the talks we’re used to from academics.

This is what it was like to hear Audre Lorde, to listen to Pat Parker, to Marlon Riggs and Dorothy Allison, and to Essex Hemphill. Cox invoked Cornel West’s words that had been a refrain when CIIS hosted an evening with him in 2010:

Justice is what love looks like in public."

Despite the Danger

All evening we’d been primed for this excitement. People began showing up two hours early looking for tickets. Tables in the lobby were piled high with information about health and legal services, legislation, and upcoming events, staffed by CIIS community partners Causa Justa, the San Francisco LGBT Center, Transgender Law Center, and TGI Justice.

I watched as old friends greeted one another and new friends were made.

Joël Barraquiel Tan, Director of Community Engagement at Yerba Buena Arts Center, later wrote that the auditorium was packed with all ages of not mostly white people, artists, and nonprofit workers, drag queens from the Stonewall Uprising, transladies in perfumed packs, a new generation of Radical Faeries, retired Queer Nationals, tuxedoed ACT UPpers, Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, adjunct professors, and Cockettes. There were at least three queer generations of Pride in the house.

Cox told the story of Islan Nettles, a trans woman in New York who was beaten into a coma when a group of men realized she was trans. Nettles died a few days after the attack. Violence is physical, verbal, and psychological. “I’ve come to believe that calling a transgender woman a man is an act of violence,” Cox said. She believes that it is her obligation to use the cultural attention surrounding her to publicly witness and remember those whose stories might otherwise be forgotten.

And she told the story of CeCe McDonald, a trans woman in Minnesota who survived a violent attack for which she served time in a men’s prison after the district attorney refused to allow a self-defense plea. Cox, who currently plays an incarcerated trans woman on Netflix’s hit show “Orange is the New Black,” is making a documentary film about McDonald and the epidemic of violence toward trans women of color.

As Cox asserted her responsibility to use her access in spite of any danger that her visibility brings her, I thought of Audre Lorde saying, “When I dare to be powerful, to use my strength in the service of my vision, then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid.”

This may be the fabulous subversive paradox of the popularity of Laverne Cox: She is given a platform by the dominant culture because she is gorgeous, glamorous, and a successful actress. But the platform on which she stands is that of a fierce thinker, political strategist, and heart-driven intellectual.

I was bullied and called names, too. And now I’m a big TV star.”

In a recent BuzzFeed interview, Cox said, “The system isn’t really set up to have these conversations about intersectionality and social justice when you’re an actress. I always feel like someone is going to come along and say, ‘OK, this has gone on for too long. We need to get rid of this girl.’”

Cox talked about moving more deeply into an articulated contextual understanding of her identity, and of that identity in the world, while in college reading Simone de Beauvoir, Judith Butler (Judy B., as Cox called her throughout the night), bell hooks, and Sojourner Truth, whose “Ain’t I a Woman?” had given title to the evening’s lecture.

This is the best-case scenario of academia: helping us to understand ourselves in the context of the world. A pedagogy of survival, of imagining possibilities for a fully embodied life, of coming together in a shared struggle for mutual survival. Dealing openly with variations in life experience and context as we dialog across those differences in the service of each other and an expanded community. What we hope for is an academia that holds in its heart the belief that a pursuit of a just world is not in conflict with the deep inquiry.

This is the best of what academia can offer. And this is what CIIS endeavors toward and wrestles with at every level—in department meetings and classes and the services offered by the counseling centers, and in the role of the University in the shifting landscape of San Francisco.

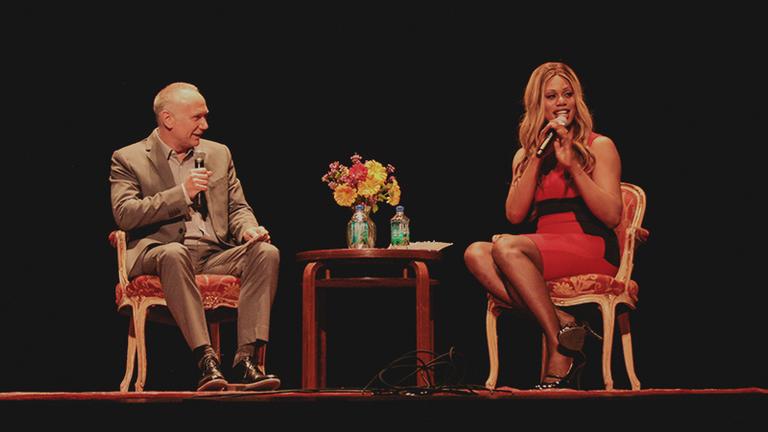

The Q and A portion of the night, moderated by Dean of Alumni Richard Buggs, allowed Cox the opportunity to talk more about her documentary about CeCe McDonald and the prison industrial complex, the criminalization of trans women sex workers, and the problematic assumptions driving the anti-condom- carrying policies: that all trans women are sex workers.

Buggs was then handed a question passed down from the audience that read:

I’m 6 and I get bullied. Since I get teased at school, I go to the bathroom in the office. What can I say to the kids who tease me?

You could hear the collective deep breath in the theater. Cox walked to the edge of the stage and called out the child’s name, squinting, looking out into the audience for the child. She motioned for the house lights to be raised. “Where are you? Come down here, honey, I’ll wait.”

The 6-year-old and family came down to the stage. So many of us in the audience were weeping. Cox looked into the child’s eyes and said, “You’re perfect just the way you are. I was bullied and called names, too. And now I’m a big TV star. Know that you are amazing and that you are chosen.”

The After-Party

The small restaurant was packed with people wanting Cox’s attention. She sat on a back-corner couch talking quietly with Jewlyes Gutierrez, a transgender 16-year-old who had been charged with battery after a fight broke out in her high school. Though Jewlyes suffered long-term bullying and, like CeCe McDonald, was defending herself, charges were not brought against her attackers.

Cox, despite a nonstop tour schedule and a looming 3 a.m. wake-up call, stayed for hours wanting to talk to everyone, not leaving anyone out.

“Tonight I’m the luckiest man on the planet,” said Richard Buggs. “She’s so lovely, so generous. Her ability to make use of suffering and the human condition in service of others is just so amazing.”

The crowd, amoeba-like, leaned and pushed against one another, trying to get to Cox. CIIS Communications Director James Martin and I were trying to filter the crowd and titrate its movements so Cox wasn’t too overwhelmed or overheated in the small space. Martin and I urged people to make space so that Miss Major, who uses a cane, could be led to Cox. But in their excitement, people weren’t listening.

“Want me to help?” asked Q Wilson, a long-time activist, and Bay Area sex educator. We nodded.

Q’s trans masculine, broad-shouldered, bleached-Mohawk African American frame carved a space through the crowd. On Q’s orders, everyone moved back, and Miss Major and the trans women helping her easily made their way to Cox. We couldn’t hear what Cox and Miss Major were saying to each other. They were looking into each other’s eyes, close to tears, holding hands. Their presence in each other’s company is evidence of so much resistance and fierce survival. Jewlyes Gutierrezwas nearby. So many generations of ferocity and kindness and possibility in the room.

I remembered something Cox wrote in The Advocate about gendered black bodies and public space: “When I was perceived as a black man, I became a threat to public safety. When I was dressed as myself, it was my safety that was threatened.”

“Hey, Q,” I said. “Yeah?” “What are you gonna do when people stop being afraid of you?” Q grinned and straightened his bowtie. “Won’t that be a fun problem?”

I thought back to where Cox had started her talk a few hours earlier, invoking Cornel West. Justice is what love looks like in public. The lingering question may be whether the love of Laverne Cox, as a performer, as a speaker and thinker, as a performative witness of the communities in which and with which she participates, will keep propelling people into dialog and toward working for justice.

Laverne Cox is the Time magazine cover woman for the week of June 9, 2014. Time subscribers can read the online version of "The Transgender Tipping Point" [paywall]. Read Time's interview with Laverne Cox.

Related Academic Programs

M.S. in Critical Sexuality Studies and Ph.D. in Human Sexuality

Related News

Your roadmap to becoming a licensed clinical psychologist through CIIS' integral, holistic approach to doctoral training and professional practice.

Discover your fit among CIIS' five counseling psychology concentrations, each offering a unique path to becoming a transformative healer.